Quiet

"The secret to life is to put yourself in the right lighting. For some it’s a Broadway spotlight; for others, a lamplit desk."

— Susan Cain, Quiet (2012)

Introduction

| Quiet | |

|---|---|

| |

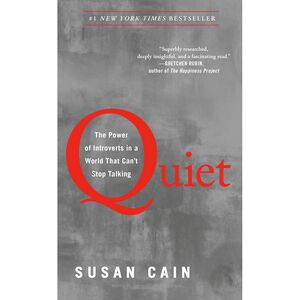

| Full title | Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking |

| Author | Susan Cain |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Introversion; Personality psychology; Interpersonal relations |

| Genre | Nonfiction; Psychology; Self-help |

| Publisher | Crown |

Publication date | 24 January 2012 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover, paperback); e-book; audiobook |

| Pages | 333 |

| ISBN | 978-0-307-35214-9 |

| Goodreads rating | 4.1/5 (as of 6 November 2025) |

| Website | penguinrandomhouse.com |

Quiet is a 2012 nonfiction book by Susan Cain arguing that modern culture undervalues introverts and examining the costs of the “Extrovert Ideal,” with practical ways to work with temperament rather than against it.[1] Drawing on social history, psychology, and neuroscience, the narrative blends research summaries with reportage to show how temperament shapes work, relationships, and learning.[2] It ranges from a Tony Robbins seminar and Harvard Business School to an evangelical megachurch—an approach Harvard Magazine describes as part scientific review, part manifesto, part self-help, and part travelogue.[3] Structured in thematic parts, the book moves from cultural history and biology to cross-cultural patterns and applied advice for couples, parents, teachers, and managers, offering strategies to match tasks to one’s optimal stimulation level.[1] The publisher lists it as a #1 New York Times bestseller and a “Best Book of the Year” pick by outlets including People, O: The Oprah Magazine, Christian Science Monitor, Inc., Library Journal, and Kirkus Reviews.[1] According to Cain’s official site and Penguin Books, the title spent eight years on the New York Times list, has been translated into over 40 languages, and has sold more than two million copies.[4][5]

Part I – The Extrovert Ideal

Chapter 1 – The Rise Of The “Mighty Likeable Fellow”: How Extroversion Became the Cultural Ideal

🎩 In 1902, in Harmony Church, Missouri, a shy high-schooler named Dale—later Dale Carnegie—looked for a way out of a bankrupt pig-farm life and discovered the magnetism of public speaking, a path that would carry him from traveling salesman to teacher and media figure. This personal arc sits against a cultural turn at the start of the twentieth century from a “Culture of Character” to a “Culture of Personality,” charted by historian Warren Susman, as cities swelled and commerce rewarded the confident. A 1922 Woodbury’s Soap advertisement asking if strangers’ eyes can be met “proudly—confidently” captures the new public mood, and popular magazines such as Success and The Saturday Evening Post taught conversation as a skill. Self-help manuals told readers to craft a palpable persona—the “mighty likeable fellow”—and business schools and sales courses spread that gospel into offices and shop floors. The shift changed hiring and courtship alike: interviews prized a polished pitch, and social life honored charm over reticence. Carnegie’s early classes and later bestsellers modeled performance as a route to advancement, reinforcing the value of being outgoing on command. Together these cues created a template for American success that equates visibility with merit. Over a century, marketing, urbanization, and mass media normalized a personality-first standard, and the resulting reward systems—grades for participation, promotions for talkers, and the commerce of confidence—privilege extroverted display and mute reflective strengths.

Chapter 2 – The Myth Of Charismatic Leadership: The Culture of Personality, a Hundred Years Later

👑 At Harvard Business School, where classroom participation drives status and grades, the incoming class each autumn runs the Subarctic Survival Situation: “2:30 p.m. on 5 October,” a floatplane has crashed near Laura Lake on the Quebec–Newfoundland border, and teams must rank fifteen salvaged items—compass, sleeping bag, axe, and more—first alone, then together, and compare their lists to an expert key on video review. One team ignores a softly spoken member with northern backwoods experience; the group’s confident talkers overrule him, and the team underperforms its best individual score, a tidy case of style eclipsing substance. Around campus, students describe a social sport of constant going-out and public speaking, and even a Wall Street Journal cartoon at Baker Library lampoons “great leadership skills” marching profits downhill. Research bridges the anecdote: in field data from a national pizza chain, Adam Grant, Francesca Gino, and David Hofmann find that extroverted managers post 16% higher profits when employees are passive, but introverted managers do better when employees are proactive. Military lore (“the Bus to Abilene”) and studies of fast talkers who get rated as smarter than their SATs justify show how performance signals can be misread. The route also includes Saddleback Church in Lake Forest, California, where a megachurch’s production scale mirrors business schools’ preference for stage-ready charisma. Institutions teach leadership as assertive display rather than careful listening. Charisma is context-bound and easily confounded with competence, and a bias toward fluency and dominance amplifies loud voices even when quiet leaders—especially with proactive teams—make better decisions.

Chapter 3 – When Collaboration Kills Creativity: The Rise of the New Groupthink and the Power of Working Alone

🤝 Steve Wozniak’s routine at Hewlett-Packard—predawn reading in his cubicle, late-night tinkering at home, and then the breakthrough on 29 June 1975 around 10:00 p.m. when the prototype printed letters to a screen—anchors the case for solitude in creation. Mid-century studies at UC Berkeley’s Institute of Personality Assessment and Research (1956–1962) found many highly creative architects, scientists, and writers were socially poised yet independent introverts, comfortable working alone for long stretches. By contrast, the contemporary “New Groupthink” elevates teamwork: open-plan offices now house over 70% of employees at firms like Procter & Gamble and Ernst & Young, while floorspace per worker shrank sharply by 2010, and schools replace rows with “pods” for constant group work. Evidence cuts against the fashion: Tom DeMarco and Timothy Lister’s Coding War Games showed a 10:1 gap between top and bottom programmers, with the best clustered in workplaces offering privacy, control, and freedom from interruption; broad reviews link open plans to lower productivity, more stress, and higher turnover. Classic lab findings on brainstorming also show nominal groups—people ideating alone—outperform talking groups, which suffer from production blocking and evaluation apprehension; even advocates of collaboration concede the need for quiet space and asynchronous tools. Collaboration is a design choice, not a virtue signal. Breakthrough work often requires uninterrupted attention and autonomy, with interaction used sparingly and at the right phase; constant exposure fragments focus and empowers dominant voices, while solitude supports deep work and original combinations. That advice is: Work alone.

Part II – Your Biology, Your Self?

Chapter 4 – Is Temperament Destiny?: Nature, Nurture, and the Orchid Hypothesis

🧬 At 2:00 a.m. on the eve of a major talk, Cain lies awake, cycling through worst-case scenarios while her partner Ken—a former UN peacekeeper—tries gallows humor that does little to quiet the dread. In 1989 at Harvard’s Laboratory for Child Development, Jerome Kagan’s team evaluated 500 four-month-old infants for forty-five minutes, exposing them to taped voices, popping balloons, colorful mobiles, and the smell of alcohol on cotton swabs. About 20% cried and pumped their limbs—the “high-reactive” group—while about 40% stayed placid as “low-reactive,” with the rest in between; years of follow-ups at ages two, four, seven, and eleven (with a gas mask, a clown, and a radio-controlled robot among the probes) showed how vigilance or ease with novelty took root. An excitable amygdala ran through the findings—elevated heart rate, dilated pupils, higher cortisol—predicting cautious, observant approaches to new people and places. At Massachusetts General Hospital’s Athinoula A. Martinos Center, Carl Schwartz later scanned members of Kagan’s cohort and found that early “high-reactive” histories left a detectable footprint in adult amygdala responses to unfamiliar faces. The “orchid hypothesis,” popularized by David Dobbs and advanced by Jay Belsky, holds that some children (often the high-reactive) wilt in harsh settings yet flourish in nurturing ones, a pattern echoed in rhesus-monkey studies and human work on the short allele of the Serotonin transporter gene. The same sensitivity that magnifies risk can, under supportive conditions, amplify empathy, conscience, and social skill. Temperament sets a bias through arousal systems like the amygdala, but outcomes depend on differential susceptibility—the ongoing exchange among genes, environments, and choice.

Chapter 5 – Beyond Temperament: The Role of Free Will (and the Secret of Public Speaking for Introverts)

🎤 Deep inside the Athinoula A. Martinos Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Dr. Carl Schwartz unlocks a room housing a multimillion-dollar fMRI and has visitors remove metal—its magnetic field is described as 100,000 times stronger than Earth’s pull. He scans late-teen participants from Kagan’s cohort, tracking amygdala responses to faces to see whether early high- and low-reactive footprints persist into adulthood. The images make visible what temperament studies imply: some brains flag novelty as threat more quickly, and that arousal competes with the working memory and attention extemporaneous speaking requires. In a Manhattan Public Speaking–Social Anxiety workshop led by Charles di Cagno, graded exposure replaces sink-or-swim, helping anxious speakers build tolerance in small, low-stakes steps. Careful preparation, topic selection rooted in genuine interest, and designed conditions—quiet warm-ups, smaller rooms, planned pauses—keep arousal in the “sweet spot” between boredom and panic. The aim is not to remake nature but to design skills and contexts so introverted strengths can surface onstage. Free-trait stretching works when tethered to values and buffered by recovery; temperament sets the preferred stimulation level, and deliberate practice and smart environments sustain performance without burnout.

Chapter 6 – “Franklin Was A Politician, But Eleanor Spoke Out Of Conscience”: Why Cool Is Overrated

😎 On 9 April 1939 (Easter Sunday) at the Lincoln Memorial, contralto Marian Anderson sings to roughly 75,000 after the Daughters of the American Revolution deny her Constitution Hall; Eleanor Roosevelt resigns from the DAR and helps move the concert outdoors, stoking a national reckoning. The portrait juxtaposes Franklin’s buoyant sociability with Eleanor’s shy, serious, conscience-driven activism, rooted in her settlement-house work on New York’s Lower East Side. Over time she becomes the first First Lady to hold press conferences, write a syndicated newspaper column, appear on talk radio, and later serve at the United Nations to help secure the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The discussion examines the American cult of “cool”—sensation seeking, easy charm, surface boldness—and how it can blind institutions to the steadier gains of sensitivity and principle. Elaine Aron’s research on sensory-processing sensitivity reframes traits often labeled “too sensitive” as deep processing and careful noticing that favor integrity over show. Rather than reject charisma, broaden what counts as leadership and moral courage. Cool is a narrow performance; conscientious sensitivity keeps attention on what matters when attention is costly.

Chapter 7 – Why Did Wall Street Crash And Warren Buffett Prosper?: How Introverts and Extroverts Think (and Process Dopamine) Differently

📉 At 7:30 a.m. on 11 December 2008, “financial psychiatrist” Janice Dorn takes a call from a retiree who has lost $700,000 by chasing and doubling down on GM stock during bailout rumors, a case she reads as reward-sensitivity run amok. Exuberance curdles into “deal fever” and the “winner’s curse,” with the AOL–Time Warner merger’s $200 billion wipeout as emblem. The reward network—nucleus accumbens, orbitofrontal cortex, amygdala—and dopamine amplify the pull of anticipated gains; experiments reveal that incidental reward cues can nudge people toward riskier bets. Extroverts, more responsive to reward, are likelier to accelerate when signals say brake, while introverts more often register threats, make plans, and stick to them. The counterpoint is Warren Buffett at Allen & Co.’s Sun Valley conference in July 1999: after weeks of preparation, he calmly warns the tech-fueled boom won’t last—his first public forecast in thirty years—and is vindicated when the dot-com bubble bursts. Under pressure, lower reward sensitivity and deliberate solitude help investors resist herding and survive volatility. A cooler reward system slows the chase long enough for analysis to catch up with emotion.

Part III – Do All Cultures Have an Extrovert Ideal?

Chapter 8 – Soft Power: Asian-Americans and the Extrovert Ideal

🌏 In 2006, Mike Wei, a soft-spoken, Chinese-born senior at Lynbrook High School in Cupertino, California, prefers listening to classmates over performing for them; he has just earned a place in Stanford’s freshman class. A few miles away, Monta Vista High School’s 2010 graduating class is about 77% Asian American, with dozens of National Merit semifinalists and a 2009 average SAT score of 1916/2400, well above the national mean—signs of a community that prizes study over show. Local voices—students like Chris, teacher Ted Shinta, and counselor Purvi Modi—describe a status hierarchy that admires studiousness, chess champions, and band kids more than cheerleaders or football players. Researcher Robert McCrae’s world map of personality depicts Asia as more introverted than Europe and the U.S., while cultural psychologist Heejung Kim argues that talking isn’t always a positive act; in think-aloud experiments, Asian American students often perform better when allowed to work quietly. Even brain-imaging work comparing Americans and Japanese shows different reward responses to dominant versus deferential postures, hinting at deep cultural scripts. From Cupertino to Stanford, Mike wrestles with louder social norms and seeks spaces—library corners, small groups—where he can be himself. Later, in a Foothill College seminar led by communications professor Preston Ni, foreign-born professionals learn how U.S. business culture rewards voice and style yet also discover an alternative path. Norms for “good participation” are not universal; environments decide which behaviors get noticed and rewarded. In settings that prize humility, restraint, and scholarship, quiet influence builds by accumulation rather than display.

Chapter 9 – When Should You Act More Extroverted Than You Really Are?

🎭 Psychologist Brian Little, a beloved Harvard lecturer, routinely bursts into high-energy classes and then disappears to a bathroom stall—the only nearby “restorative niche” where he can lower his arousal and regroup. Little’s Free Trait Theory explains how people can act out of character in service of “core personal projects,” such as teaching, caregiving, or a cause, without becoming someone else. The lecture hall story shows the cost of sustained performance: after the show, he hides his shoes from chatty passersby and breathes until his nervous system settles. Around this, practical guardrails emerge: schedule solitude before and after high-stimulation events, script openings for tough conversations, and choose media—email, memos, one-on-ones—that fit the task. This is not a call to “fake it” indefinitely or refuse all adaptation; it is a plan to flex with intention and then recover. Acting out of character works when tethered to values and buffered by routine recharging; sustainable peak work alternates strategic display with honest retreat.

Chapter 10 – The Communication Gap: How to Talk to Members of the Opposite Type

🗣️ Greg, a gregarious music promoter who lives for Friday dinner parties, and Emily, a reserved staff attorney at an art museum who longs for quiet weekends, clash not only over calendars but over styles—Greg pushes and raises the intensity, Emily withdraws and flattens her tone to avoid escalation, which he reads as indifference. Complementary misreads crop up at home and at work: extroverts “talk to think,” prefer fast turn-taking, and seek energy from a room; introverts “think to talk,” favor depth and pace, and need recovery time that can look like avoidance. Partners and teammates can trade formats (smaller groups, defined end times), pre-brief before big events, and use quieter channels—notes, walks, or agenda-driven check-ins—to surface views without a shouting match. The aim is not to split the difference but to tailor context to the task and people. When both sides name needs and design around them, emotional safety and timing matter more than volume, and style stops masquerading as character.

Chapter 11 – On Cobblers And Generals: How to Cultivate Quiet Kids in a World That Can’t Hear Them

🧒 A Mark Twain parable about a cobbler who, had he been a general, would have been the greatest of them all frames hidden potential in quiet children. A University of Michigan case from child psychologist Jerry Miller follows “Ethan,” a gentle seven-year-old with driven, extroverted parents who mistake his caution for weakness and try to drill “fighting spirit” into him. Across classrooms and playgrounds, the text differentiates healthy introversion from shyness and anxiety, urging adults to avoid pathologizing a child’s warm-up time. Concrete moves follow: seat quiet kids away from high-traffic zones, use pair work before full groups, give advance notice for presentations, and let them practice privately before performing publicly. Praise effort over volume, build skills like eye contact and turn-taking without forcing nonstop participation, and create “restorative niches” at school and home. Developmentally, gradual exposure—not overprotection or bulldozing—builds confidence and competence. The larger aim is fit: align environments with temperament so strengths emerge on their own timeline.

—Note: The above summary follows the Crown hardcover edition (24 January 2012; ISBN 978-0-307-35214-9; 333 pp.).[1][6]

Background & reception

🖋️ Author & writing. Susan Cain is a former Wall Street corporate lawyer and negotiations consultant who later turned to writing; she studied at Princeton and Harvard Law School.[7][8] The book mixes interviews and case studies with findings from psychology and neuroscience, taking readers to a Tony Robbins seminar, Harvard Business School, and a megachurch to illustrate how environments reward extroversion.[3] Its voice is journalistic and reflective, aiming to translate research into usable advice for readers at work and at home.[2] The first U.S. edition was published by Crown on 24 January 2012 (333 pp.).[1][9] Her 2012 TED talk, “The power of introverts,” helped amplify the book’s ideas beyond print.[10]

📈 Commercial reception. The publisher lists Quiet as a #1 New York Times bestseller; Cain’s official site adds that it spent eight years on the list and has been translated into more than 40 languages.[1][4] Penguin Books reports sales of over two million copies worldwide.[5] On the trade-paperback charts, Publishers Weekly logged sustained performance in late 2013–early 2014, including a peak at No. 2 on 4 November 2013 and, in its year-end analysis, the longest tenure of any 2013 bestseller.[11][12]

👍 Praise. Kirkus Reviews praised Cain as “an enlightened Wall Street survivor” making a compelling case for the value of solitude and careful thought.[2] The Guardian called it “an important book—so persuasive and timely and heartfelt it should inevitably effect change in schools and offices.”[13] Fortune recommended the book in its “Weekly Read,” arguing that organizations benefit when leaders listen more and talk less.[14]

👎 Criticism. In its pre-publication review, Publishers Weekly said some claims were advanced “with insufficient evidence,” even as it praised Cain’s portraits and reporting.[15] A dual The Guardian review warned that the book sometimes overgeneralizes and risks a self-congratulatory tone about introverts.[16] Psychologist Ravi Chandra criticized the chapter on Asian-Americans for leaning on stereotypes and underplaying racism’s effects.[17]

🌍 Impact & adoption. In workplaces, Cain partnered with Steelcase to create “Susan Cain Quiet Spaces,” a product line of focus rooms and furnishings launched in 2014 and recognized at NeoCon.[18][19][20] In education, her Quiet Revolution launched the Quiet Schools Network to train “Quiet Ambassadors” and adapt classroom practices for different temperaments.[21] Media exposure—especially her 2012 TED talk—continues to carry the book’s ideas into company programs and curricula.[10][22]

Related content & more

YouTube videos

CapSach articles

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "Quiet by Susan Cain". Penguin Random House. Penguin Random House. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Quiet". Kirkus Reviews. Kirkus Media. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Susan Cain foments the "Quiet Revolution."". Harvard Magazine. Harvard Magazine. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Quiet – Susan Cain". Susan Cain. Susan Cain. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Quiet". Penguin Books UK. Penguin Books. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking". Google Books. Crown. 24 January 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Susan Cain: 'Society has a cultural bias towards extroverts'". The Guardian. 31 March 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Susan Cain '89 on the Undiscovered Value of Bittersweet Thinking". Princeton Alumni Weekly. Princeton University. 25 April 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Quiet : the power of introverts in a world that can't stop talking". Davenport Public Library Catalog. Davenport Public Library. Retrieved 6 November 2025.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "The power of introverts". TED. TED Conferences. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Publishers Weekly Bestseller Lists — Trade Paper, 25 November 2013". Publishers Weekly. 25 November 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Behind the Bestsellers, 2013". Publishers Weekly. 10 January 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking – review". The Guardian. 22 March 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Why silence is golden". Fortune. 10 February 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking". Publishers Weekly. PWxyz, LLC. 31 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking – review". The Guardian. 18 March 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Susan Cain's Quiet: Is Asian American Silence "Golden"?". Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers. 27 June 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Susan Cain Quiet Spaces". Steelcase. Steelcase Inc. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Steelcase And Susan Cain Design Offices For Introverts". Fast Company. 3 June 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "Steelcase Receives Top Honors at NeoCon 2014". PR Newswire. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "About the Quiet Schools Network" (PDF). Quiet Revolution. Quiet Revolution LLC. May 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ↑ "'Quiet' author Susan Cain on managing introverts". Fortune. 3 June 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2025.